“According to ancient science, one or two forces are insufficient to produce a phenomenon. A third force must be present, without which the first two can never produce anything at all… The first force may be called “active” or “positive”; the second, “passive” or “negative”; the third, “neutralizing.” (Gurdjieff, In Search of Being, Shambhala Publications, 2019, p61)

Observing difficult circumstances in our lives and conflict in our society, it becomes obvious that opposing forces eventually reach an equilibrium resulting in a ying/yang variety of stalemate. Two sides of the same coin; strengthening one side leads to the opposing side gaining force. Only when a neutralizing third force is able to produce a metamorphosis or a paradigm-changing substrate may a real and sustainable solution be constructed.

A delightful conversation in a noisy coffee shop with Maria Foscarinis, author of And Housing for All, The Fight to End Homelessness in America (Prometheus Books, 2025), led to my being thoroughly educated, (probably an overstatement: more like abruptly enlightened) on the history, politics and extent of homelessness in the USA.

This took place while I was in the midst of digesting Gurdjieff’s In Search of Being, hence the irresistible urge to fuse the two mind-bending lessons into one and attempt to apply the “Law of Three Forces” to the issue of Homelessness.

In this case, the “active” force may be distilled or condensed to that of “Affordable Housing Demand” and the “passive” resisting force to “Lack of Affordable Housing”. This results in Homelessness as the issue or as the proverbial coin with two (active and passive) faces. The construction of a neutralizing force to this dilemma requires a dispassionate look into what can only be described as societal failure.

It is very easy, practically automatic, to view this phenomenon as another partisan political talking point. As such, it is very easy to fall into the emotional “poster child” exchange dynamic which only increases the volume of the blame game, distracting from any fundamental solution building. It is behind this smoke screen where special interests hide and thrive.

The Affordable Housing Demand is created by three categories generally accepted by all parties:

• People who have made questionable life decisions and those with mental illness,

• People who are physically disabled and have need of assistance, and

• People and families facing financial difficulty.

• I would also add Starter Families within this grouping, although they have not traditionally been part of the discussion.

A shocking revelation which puts the entire situation in perspective is the fact that current vacant housing just sitting ready for occupancy far outweighs the demand for housing.

The Lack of Affordable Housing seems to be created by:

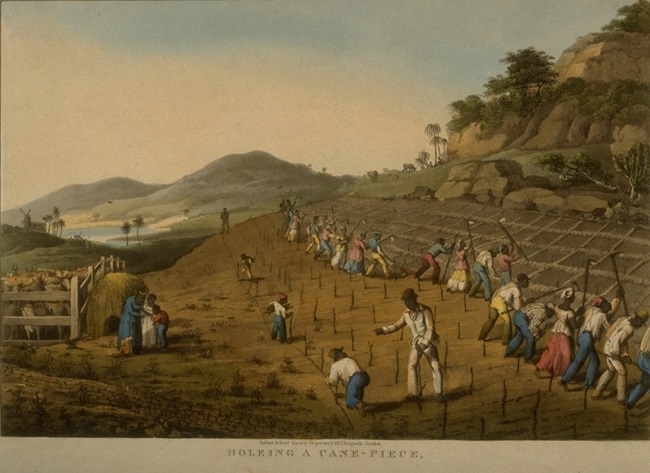

• Housing as a Commodity Investment by corporations, equity funds and investment firms restricting supply of ready-to -occupy vacant housing as a strategy to maintain high rental and purchase costs, while simultaneously increasing the value of their holdings.

• “Pay per Play” Governmental Predisposition or “Wink and Nod” through approving programs but not allocating resources, allowing non-compliance of law and favoritism towards lobbies over citizens.

• Gentrification of traditional neighborhoods and the advent of Business Improvement Districts (BIDs) displacing lifelong residents.

• Zoning, regulations and Home Owners Associations (HOAs), all focused on maintaining property values.

Not all of the little funding made available for assisting the homeless is efficiently applied, which adds to the problem and fuels the opposition to “public assistance”. Homelessness has become an Industry by service providers, a “cottage industry” and non-governmental organizations. Just as any growth industry will prioritize growth of their client base and economic leverage over resolving the problem and then fading away. High overhead and corruption need to be transparently addressed and dealt with. We do seem to maintain the practice that is best encapsulated in the statement, attributed to various historical figures, regarding USA support to then Nicaraguan dictator, Anastasio Somoza Garcia, “He’s a son of a bitch, but he’s our son of a bitch”. The ranks close firmly while at war and all signs of impropriety must be ignored.

Independent of the criticism leveled, and rightfully so, at specific cases of abuse of the system and corruption in the execution of programs, what stands out clearly is the fact that the Demand is created by people- flesh and blood people, and the Lack is created by systems and structures built for specific economic interests by individuals and groups, but without any human qualities of their own.

Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness are held high as inalienable rights of citizens. While a corporation or equity fund does not have the attributes necessary to embody these lofty concepts, a series of historical Supreme Court ruling have supported certain “citizen rights” to corporations, which has opened the doors to very questionable application of the law, including even the right to representation within our organization of government.

“Am I a Citizen?” is a powerful reproof presented as a question, in chapter nine of Foscarinis’ book, as homeless citizens are treated as outcasts, even alien, given that identification itself is firmly linked to holding a physical address. When an equity fund can prove citizenship rights easier than a human born within the country, it’s time rethink our social contract.

You tuber Offended Outcast takes us into the world of retirees who have no where to go. “Survival looks like trespassing” and “Unprofitable people are dangerous” are just a few of the incisive themes in Offended Outcast’s forceful and informative videos.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1944, proposed a Second Bill of Rights which included the right of every family to a decent home. “We cannot be content, no matter how high that general standard of living may be, if some fraction of our people—whether it be one-third or one-fifth or one-tenth—is ill-fed, ill-clothed, ill housed, and insecure.” (State of the Union Message to Congress. January 11, 1944).

It is well worth reading the entire text of FDR’s speech to Congress, before irrupting into the “Obligation of Government” versus the “Bootstrap Upward Mobility” argument. The rights proposed clearly start off with “useful and remunerative jobs”, the right to earn, sell and trade “in an atmosphere of freedom from unfair competition and domination by monopolies…”

The automatic rejection over economic costs of acknowledging (not granting, but acknowledging) these rights does not have a firm foundation. Furthermore, the “problem” does not go away because it is denied. Studies show, and certainly more studies should be done objectively, that the economic cost of criminalizing homelessness and dealing with the ensuing social disaster is higher than addressing the issue in a dignified manner. The emotional and developmental damage done to homeless children, tragic in itself, only contributes to a chronic and repetitive cycle of despair generation after generation. Even setting aside social concerns, an objective economic review would project that every homeless person out there is a potential productive worker and a guaranteed consumer. It’s an investment.

Successful working models exist and should be examined without the automatic partisan political filter. True opposition to solving homelessness does not come from that smoke screen, but rather from faceless non-human entities created to harvest economic wealth regardless of infringing basic rights of our fellow citizens.

The experience of Houston’s “Housing First” program, through groups like “The Way Home” is worth studying for replication for the difficult emergency, mental health and chronic disability cases. The Community Land Trust (CLT) is a promising option as solution for economic hardship cases. For this option, the Trust purchases land and develops low-income housing for sale. While the house is owned by the buyer, the trust retains ownership of the land, with a long-term lease to the homeowner. If the owner wishes to move on and enter a less restrictive housing solution, they can sell under conditions of affordability to a new buyer. Practical solutions do exist, and importantly are working, albeit on a small scale.

The “neutralizing third force” that must be brought to bear for the homelessness dilemma is the acknowledgment of unalienable human rights, as proposed by FDR in 1944, and a clear definition of exactly what is meant by “We the People.” Have we foregone the representative democracy experiment for a caste structure with participation of and enforced by faceless systems? Blaming the “system” is the epitome of weakness and lack of responsibility.

The second Hermetic principal of “As above, so below” or in this case as “As without, so within” reminds me to peer into the mirror of the homelessness phenomenon in order to identify why this particular theme resonates with my being.

A recurring nagging thought, obviously unresolved, arises in my consciousness regarding the nature of “human being” versus “human doing” within the context of self-worth and personal values. Productive activity and “doing responsibly” boosts my self-image and allows “fitting in” with the crowd, while “being lazy” brings guilt and shame. Even attempting to remedy this imbalance by leaving a steady job to “putter around” in the shop, does not eliminate the hamster-wheel mentality carried deep inside. I catch myself focusing even more on productivity. The “active” need for balance or desire to turn energy inward faces off against the “passive” ingrained work ethic which places economic security over the development of basic human qualities. In doing so, I treat myself as a “human resource”, converting into my own self-imposed “equity fund”, denying attention and development to my “unproductive” side- the homeless unembraced human qualities. Reconciliation of this will require a redefinition of self and a restructuring of priorities in which the “doing” is a result of a free and independent “being”.

The mirrored reflection, practically a holographic overlay between the inner and outer worlds, hinted at by many sources, is a challenging realization. On both levels, “doing” is in essence a non-wavering focus on competition, while “being” depends upon and creates cooperation. Our genuine identity as an individual, as well as a nation, must embody humanity and being over the temporal activity of doing.