Northern Morazán is a remote border region in El Salvador. It is an area where the dimensional divide between education and development is very clearly demonstrated. Hundreds of local young people graduate from “vocational school” each year and enter “the real world” without the basic skills needed to face daily obstacles and to seize the occasional opportunities when presented.

High school in El Salvador has both a two-year general program as the route to university studies and a three year vocational option. Most rural students opt for vocational studies, as they lack the financial resources involved not only for tuition but for travel, lodging and living expenses to go to university. The problem is that most rural high schools have only one, and at the most two, vocational options. The high school in Perquín, Morazán provides Accounting and Secretary as the two vocational options, from which over one hundred students graduate each year. The obvious contradiction is that northern Morazán, statically the poorest area in El Salvador has little to no openings for these positions. The other difficulty is that the educational curriculum for these specialties is outdated, requiring the graduate who does find employment to relearn their skills once again.

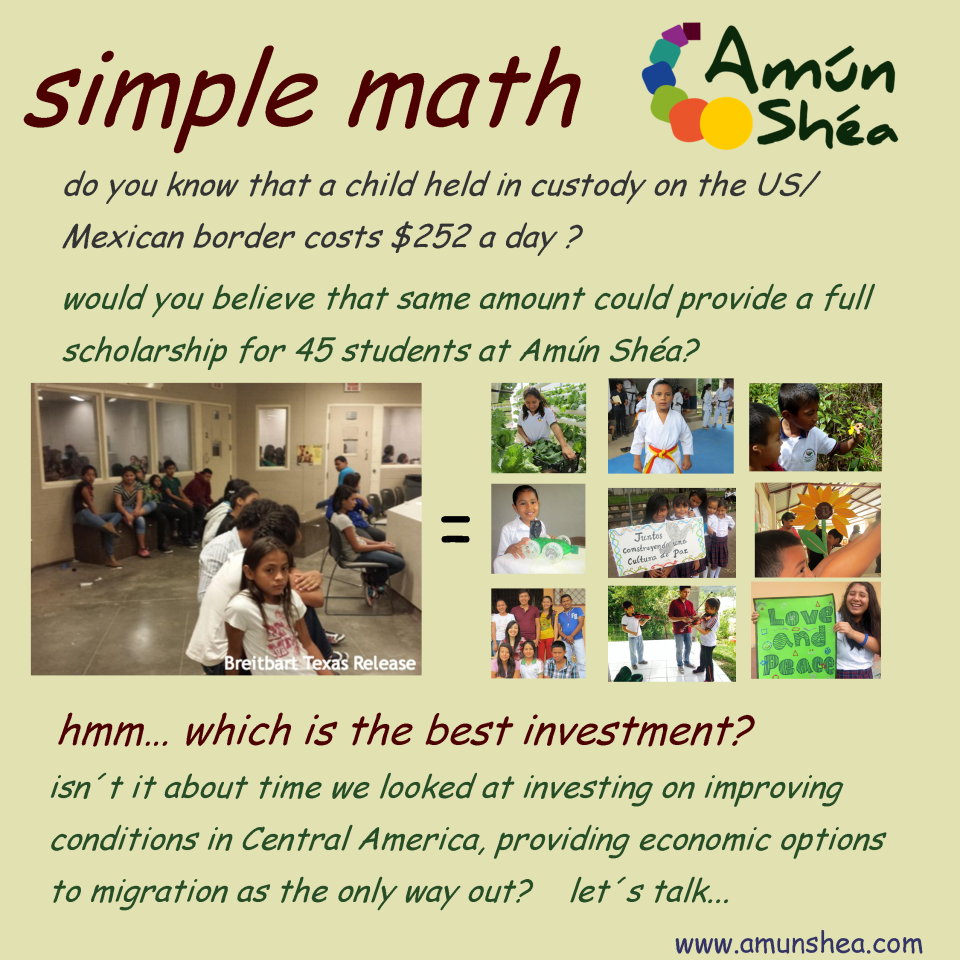

Actually, a vanguard educational system should be the most significant means available to lead development and fight poverty in remote areas of developing countries. However, the traditional separation of formal education from socioeconomic developmental programs results with both falling far short of essential expectations and having little impact on real living conditions. It is indeed a sad truth that expectations regarding both program areas have plummeted, as the status quo of helplessness reigns supreme.

Attempts to effect change are often viewed as unrealistic and discarded as impractical theories. Programs too often are funded only because tradition and political correctness mandates tolerating this social burden, even though the probability of failure can easily be assumed.

Both, may we say, industries, have become institutionalized and increasingly specialized, conceivably to their own detriment. There is an obvious flaw in educational programs that are focused on forming excellent employees but work within a reality of very few job opportunities. Equally, developmental programs often mistakenly assume that the beneficiary population has sufficient knowledge or has the capacity to assimilate new techniques and productive innovations, creating frustration and inefficiency during program implementation and operation.

Very often these educational and developmental programs operate side by side without ever coming into contact with each other. Ostensibly they are all inclusive and mutually exclusive. Unfortunately, neither has managed to solve the social or economic woes in rural areas of developing countries. Both focus on content, knowledge, tools, resources and projected outcome. It is striking that neither consider attitude, self-motivation and self-realization to be basic components in their strategic planning and methodology.

A credible study of the long history of charity programs, reconstruction projects and readily available technical training courses will reveal a high degree of passivity and dependence on outside intervention as a direct result of their implementation. Development projects actually become a means of subsistence in and of themselves without hope of actually originating self-perpetuating productiveness and sustainability. The projects themselves become the employer and the organizations are often converted into a type of family business. Within this setting, traditional education has no clear purpose and therefore offers very little beyond simply keeping the children occupied while parents are working. It could essentially be said that these areas are primary components (purposely or not) of the Poverty Industry, in that “Education” provides the beneficiaries for continuous “Development” which maintains the demand for perpetual assistance and expert intervention.

Constructive socioeconomic change requires integrating the technical capacity focus of development with motivation or positive change in attitudes which are developed through appropriate educational methodology. This implies bringing the two programs together in a way that will enhance both. It requires providing education with a purpose for its existence. It means channeling development through those with interest, willingness and the capacity to assimilate innovative programs. It will provide a support structure to development and coverts education into a relevant, meaningful activity.

Amún Shéa, Center for Integrated Development in Perquín, Morazán is an example of the needed integration, with a curriculum that strives to bridge the dimensional split between academics and development. This is done with hands-on participation by the students in building solutions to local developmental hurdles. Beginning in 2008 with kindergarten through third grade, the program has expanded one grade per year, reaching ninth grade this year (2014.) Accreditation for High School next year is in process with the Salvadoran Educational Ministry.

Amún Shéa stands out from the Salvadoran norm in several concrete ways. The Amún Shéa program runs from 7:30 am to 3:00 pm, practically doubling the half-day public education system. Whereas the methodology in the public system is limited to the teacher copying material from a textbook to the chalkboard (whiteboard now, in some cases) and the student copying that same information into their notebook, our problem-based methodology integrates current and developmental concerns into the subject matter.

As the school runs a full day and nutritional-related health deficiencies within the area are alarming, Amún Shéa incorporates a complete nutrition program which provides nourishing meals, nutrition training, cooking lessons, vegetable farming, fishing farming and hygiene training. Coordinated with the USA-based organization GlobeMed, the objective of the program is to go beyond providing the daily snack and lunch to each student to actually modifying eating habits and diet within the community, beginning with the families of the students. As well, this activity opens the opportunity for families to learn from the program and implement vegetable gardening and fish farming as a business enterprise, which helps broaden the local production base from subsistence basic grains.

Amún Shéa students take on real-world problems for their scientific investigation projects. In one case, the sixth grade investigated the local municipal water supply after experiencing firsthand in their homes the indication of contamination within the distribution system. They traveled to the water source of the system, high in the neighboring Honduran mountains, interviewed the inhabitants living around the source and inspected the source. They then inspected the filtration plant, tanks and distribution system. They uncovered lapses and gaps of responsibility between the municipality and local health authorities. In the end, their investigation forced improvements in the water system for over 3,000 people.

Creation of business plans is another exercise for the integration of real-world situations into the subject material. Several small enterprises have germinated from this process, as parents are convinced of the viability by their child´s work.

Cultural research and investigation as a means of building community and personal identity is an elemental part of the program. Collecting testimony from senior citizens regarding past events, practices and local history, researching local legends and lore, and searching out traces of indigenous roots all assist in personal orientation. In this aspect, not only the past is covered, but current tendencies as well, including immigration, economic activities and opinion polls.

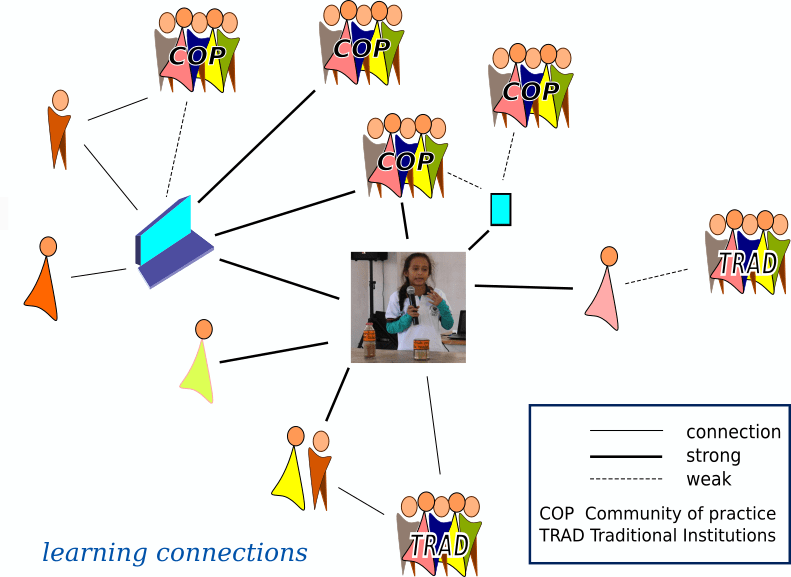

Each student is equipped with a Personal Learning Environment, basically the digital tool-kit and portfolio they will use and further develop throughout their lives. This emphasis on digital tools and resources actually levels the playing field for our students, giving them access to the same information and processes as students in more favorable conditions. It also compensates for the lack of locally available information in needed areas of technical study.

Integration of education and development is the key to initiating positive socioeconomic changes. Its success will depend on the extent that real-world application is implemented throughout the process.